The Terrorist's Handbook, by David Schulz,

LightRailWorks Press, ISBN# 978-0-9828666-1-0,

80 pages, Full Color, Digital Press (Indigo),

Perfect-bound, 10.5 x 7.75″, edition of 100, 9/11/11.

This edition is Sold out.

![]()

Throughout the summer of 2011, I made a series of walks in public places in New York City. The walks were concentrated on/in/near major infrastructural elements, such as bridges and subways. During the walks, I made photographs that sought to explore ways that these elements frame our perceptual experience, allowing for a conversion of our quotidian moments into brave navigational conquests of space and understanding. This exploration grew out of my interest in how walking relates to seeing. On each walk, I remained on public paths, platforms, and sidewalks, and stayed away from all "no-trespassing" zones. Similarly, I never photographed in areas prohibiting photography. However, it became clear early on that my simple walking and photographing was a gesture inciting grave suspicion. Each time I photographed, I was stopped by the police, told to erase my images, and hand over my identification. I was asked, "why was I photographing the bridge?" and "what was I doing so far from my neighborhood?"

Now, Google makes it possible to traverse the very same paths and streets my feet carried me on, I can make unlimited screenshots from my virtual walks, free from police interrogation. But somehow, placing myself physically in that space provokes investigation. One can easily see how vulnerable a city is, and that walking in physical space can be a creative act that transforms the walker into a producer through interaction with other people/users. The means of behavioral control in cities are countless, from architectural design to "education" to police enforcement. And one of the biggest challenges faced by our police department in this country is how to negotiate with citizens who are not breaking the law, but who are involved in suspicious activities. The tremendous gray area surrounding photography in "sensitive" areas in urban centers is a battleground that many choose to ignore, even though they may engage with it on a daily basis, complicit in the formation of value-systems that determine what exactly it is that defines "suspicious activities."

As my project evolved, I discovered an online document called the "Terrorist's Handbook" which was created by an unknown author sometime in the last 30 years, edited by countless readers, and freely available on several websites. It consists of recipes for bombs, explosives, and DIY "terrorist" strategies that will disrupt our systems. I began contextualizing my photographs within its structure and found the connections between bomb-making and walking/photographing to be poignant. Other ephemera, such as transcripts of conversations between myself and law-enforcement officials are included on pages within my book.

It is now the 10th-year anniversary of 9/11, and for the week preceding the day of memorial, there has been a constant noise of reporting on possible terrorist activity. Al Qaeda's number two official has supposedly just been imprisoned (and 10 more have taken his place). We are informed of two american citizens of Arab ancestry leaving Afghanistan, traveling through several countries, and ultimately entering the U.S. with the intention of setting off a bomb. How do we know this? A guy in Afghanistan heard it second or third-hand from someone else that this was happening. In Manhattan, police checkpoints have been set up and motorists are detained in traffic. The city has become a giant stage for the perpetual unveiling of terrorist plots, both imagined and real, as we remain speechless by the act and absolute unpredictability of 2 planes flying into the former World Trade Center.

I am reminded of the morning before 9/11 when I awoke at 4:30am, unable to sleep and so got out of bed and made my way to Red Hook, Brooklyn. Red Hook was (and still is) an aberrant neighborhood in New York City, not having access to the subway system. One has to drive, take a bus, or walk down from Carroll Gardens or Park Slope. Its century-old buildings and piers reflected its former ties to New York Harbor and the shipping industry, former bars along Conover Street catered to old sea salts still living in the area. I remember a pack of wild dogs running in the neighborhood. On the morning of 9/10/01, I found myself drawn to the piers leading out into the harbor facing downtown Manhattan and the World Trade Center, which I contemplated and photographed for several hours that morning, unaccosted by police. 24 hours later, those buildings were gone.

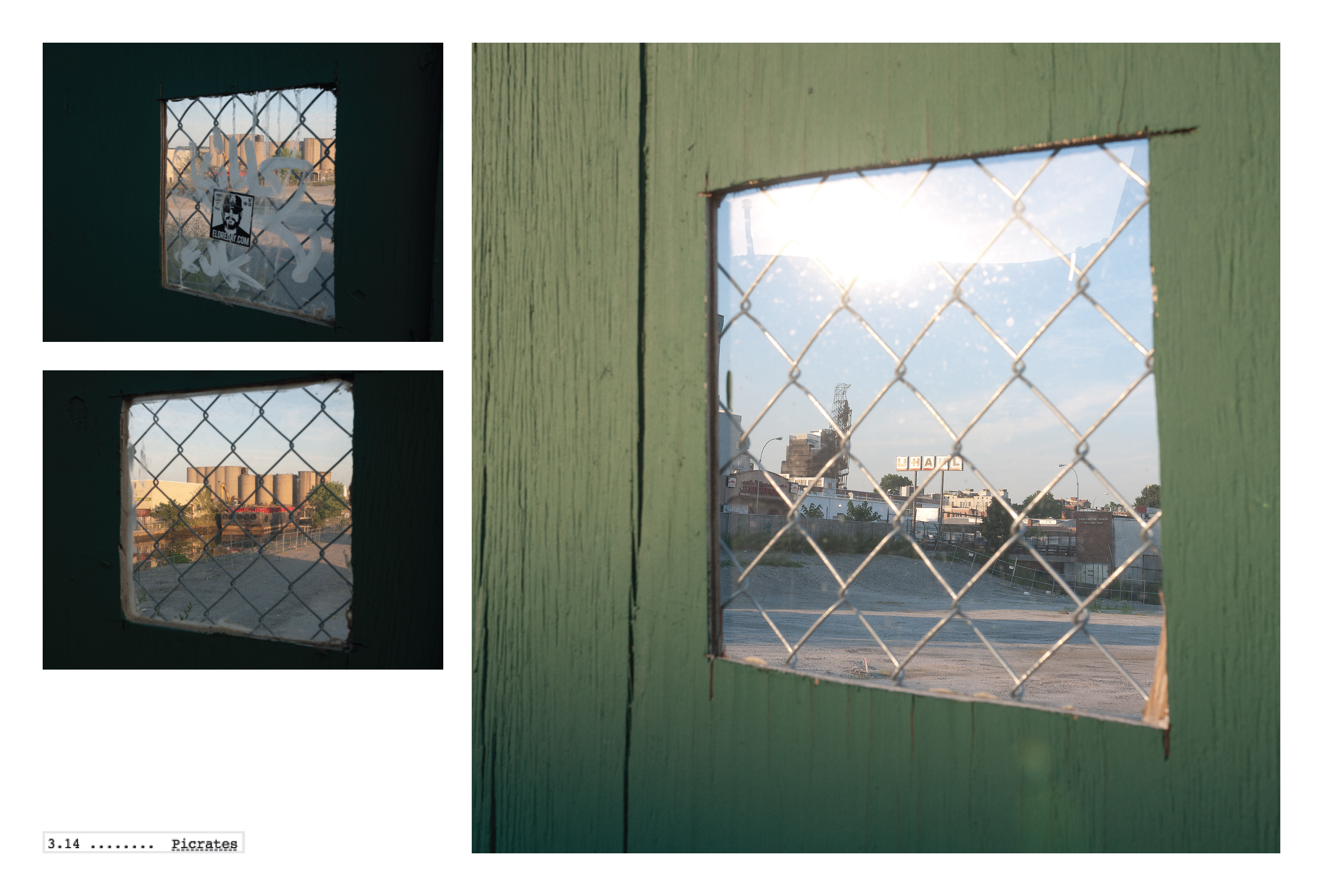

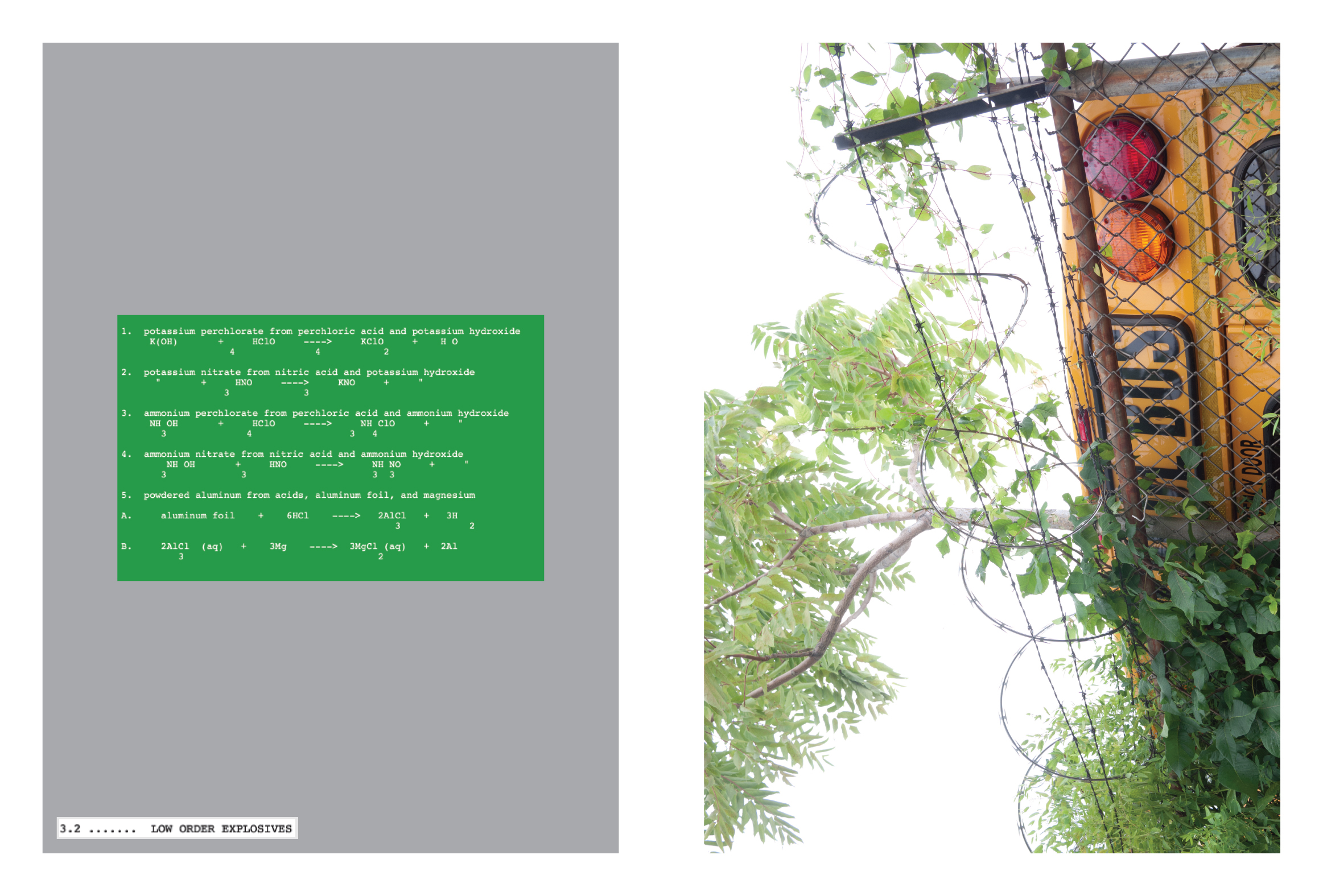

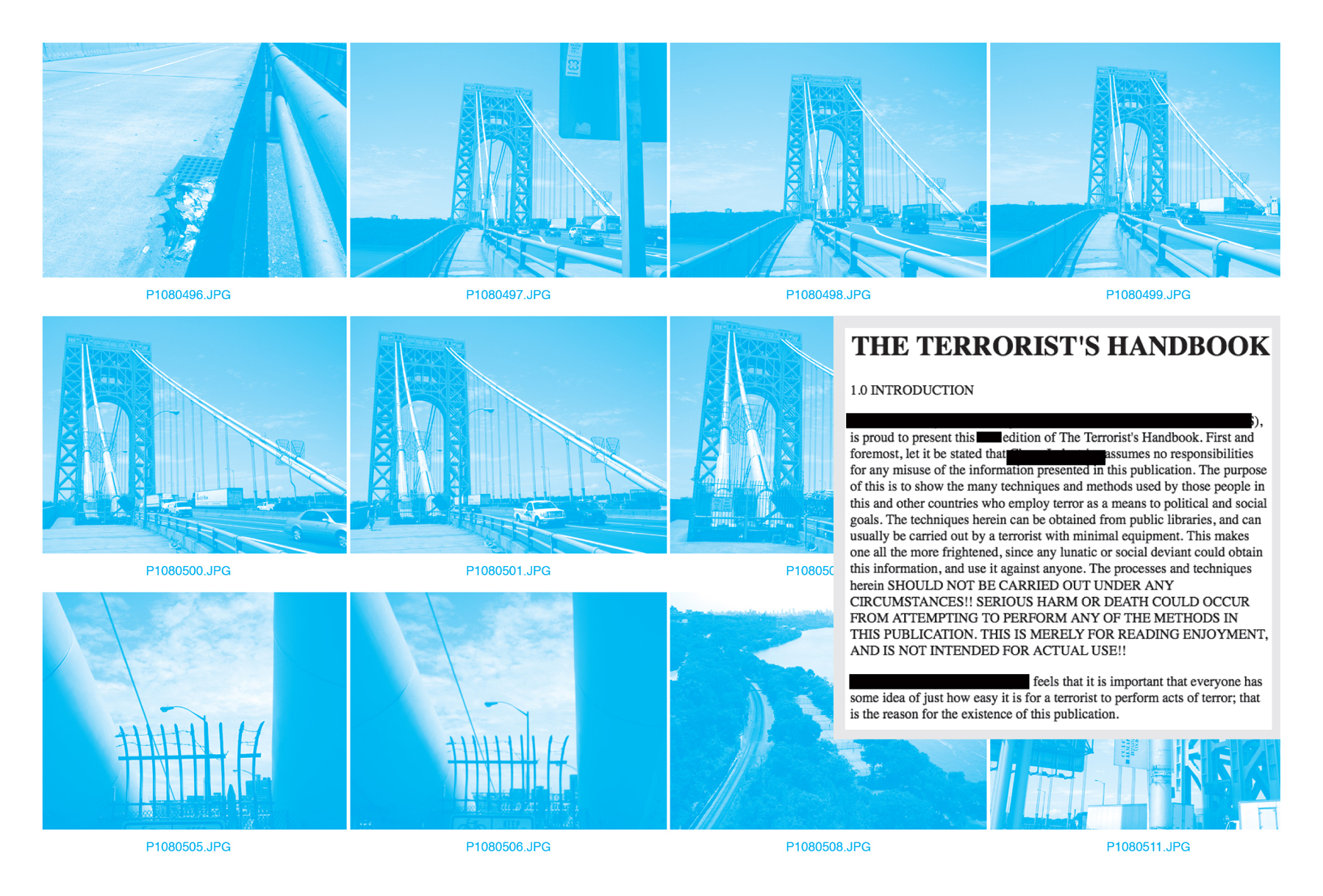

Images pictured above and below: Double page spreads from The Terrorist’s Handbook.

![]()

![]()

![]()

LightRailWorks Press, ISBN# 978-0-9828666-1-0,

80 pages, Full Color, Digital Press (Indigo),

Perfect-bound, 10.5 x 7.75″, edition of 100, 9/11/11.

This edition is Sold out.

Throughout the summer of 2011, I made a series of walks in public places in New York City. The walks were concentrated on/in/near major infrastructural elements, such as bridges and subways. During the walks, I made photographs that sought to explore ways that these elements frame our perceptual experience, allowing for a conversion of our quotidian moments into brave navigational conquests of space and understanding. This exploration grew out of my interest in how walking relates to seeing. On each walk, I remained on public paths, platforms, and sidewalks, and stayed away from all "no-trespassing" zones. Similarly, I never photographed in areas prohibiting photography. However, it became clear early on that my simple walking and photographing was a gesture inciting grave suspicion. Each time I photographed, I was stopped by the police, told to erase my images, and hand over my identification. I was asked, "why was I photographing the bridge?" and "what was I doing so far from my neighborhood?"

Now, Google makes it possible to traverse the very same paths and streets my feet carried me on, I can make unlimited screenshots from my virtual walks, free from police interrogation. But somehow, placing myself physically in that space provokes investigation. One can easily see how vulnerable a city is, and that walking in physical space can be a creative act that transforms the walker into a producer through interaction with other people/users. The means of behavioral control in cities are countless, from architectural design to "education" to police enforcement. And one of the biggest challenges faced by our police department in this country is how to negotiate with citizens who are not breaking the law, but who are involved in suspicious activities. The tremendous gray area surrounding photography in "sensitive" areas in urban centers is a battleground that many choose to ignore, even though they may engage with it on a daily basis, complicit in the formation of value-systems that determine what exactly it is that defines "suspicious activities."

As my project evolved, I discovered an online document called the "Terrorist's Handbook" which was created by an unknown author sometime in the last 30 years, edited by countless readers, and freely available on several websites. It consists of recipes for bombs, explosives, and DIY "terrorist" strategies that will disrupt our systems. I began contextualizing my photographs within its structure and found the connections between bomb-making and walking/photographing to be poignant. Other ephemera, such as transcripts of conversations between myself and law-enforcement officials are included on pages within my book.

It is now the 10th-year anniversary of 9/11, and for the week preceding the day of memorial, there has been a constant noise of reporting on possible terrorist activity. Al Qaeda's number two official has supposedly just been imprisoned (and 10 more have taken his place). We are informed of two american citizens of Arab ancestry leaving Afghanistan, traveling through several countries, and ultimately entering the U.S. with the intention of setting off a bomb. How do we know this? A guy in Afghanistan heard it second or third-hand from someone else that this was happening. In Manhattan, police checkpoints have been set up and motorists are detained in traffic. The city has become a giant stage for the perpetual unveiling of terrorist plots, both imagined and real, as we remain speechless by the act and absolute unpredictability of 2 planes flying into the former World Trade Center.

I am reminded of the morning before 9/11 when I awoke at 4:30am, unable to sleep and so got out of bed and made my way to Red Hook, Brooklyn. Red Hook was (and still is) an aberrant neighborhood in New York City, not having access to the subway system. One has to drive, take a bus, or walk down from Carroll Gardens or Park Slope. Its century-old buildings and piers reflected its former ties to New York Harbor and the shipping industry, former bars along Conover Street catered to old sea salts still living in the area. I remember a pack of wild dogs running in the neighborhood. On the morning of 9/10/01, I found myself drawn to the piers leading out into the harbor facing downtown Manhattan and the World Trade Center, which I contemplated and photographed for several hours that morning, unaccosted by police. 24 hours later, those buildings were gone.

Images pictured above and below: Double page spreads from The Terrorist’s Handbook.